Taking In Food Properly Can Help You Avoid A ‘Leaky Gut’

There’s something we all do every day, but we may not know why we do it, what’s involved and how integral it is in our lives.

Eating isn’t just about wolfing down food to keep us alive. It actually involves a very complex biological process that affects EVERY aspect of our lives.

Food is the source of the calories we need to survive, but also provides important nutrients and dictates to our bodies how we will respond to what we eat.

Highly processed, “inflammatory” foods set off a local inflammatory response that leads to “leaky gut” (increased intestinal permeability). When this occurs, the other membranes in the body become leaky too — our blood vessels and the blood-brain barrier, for example, are two key membranes that begin to have problems functioning well.

As an expert in Functional Medicine, I often tell patients to envision their bodies as a house on fire after an inflammatory meal (or years of inflammatory meals). I’m also speaking from personal experience. For many years, when eating a doughnut, my ears would become bright red and warm to the point they were almost painful. Could my body have been any more explicit in telling me what that type of food was doing to my body?

When eating whole, natural foods that are not heavily processed and preserved, they are informing our bodies that this is not inflammatory, and there’s no local inflammation and inflammatory cascade.

Similarly, how much we eat also provides information to our bodies. When eating too little, there’s weight loss both from fat stores and a decrease in lean body mass — muscle — that is difficult to rebuild, and is what serves to protect us from any attack (think pneumonia, a broken hip or viral infection). If we eat too much, the excess calories can worsen the inflammatory response, insulin resistance and obesity, etc.

So, Steps 1 & 2 of How to Eat is what type of food and how much of it to eat.

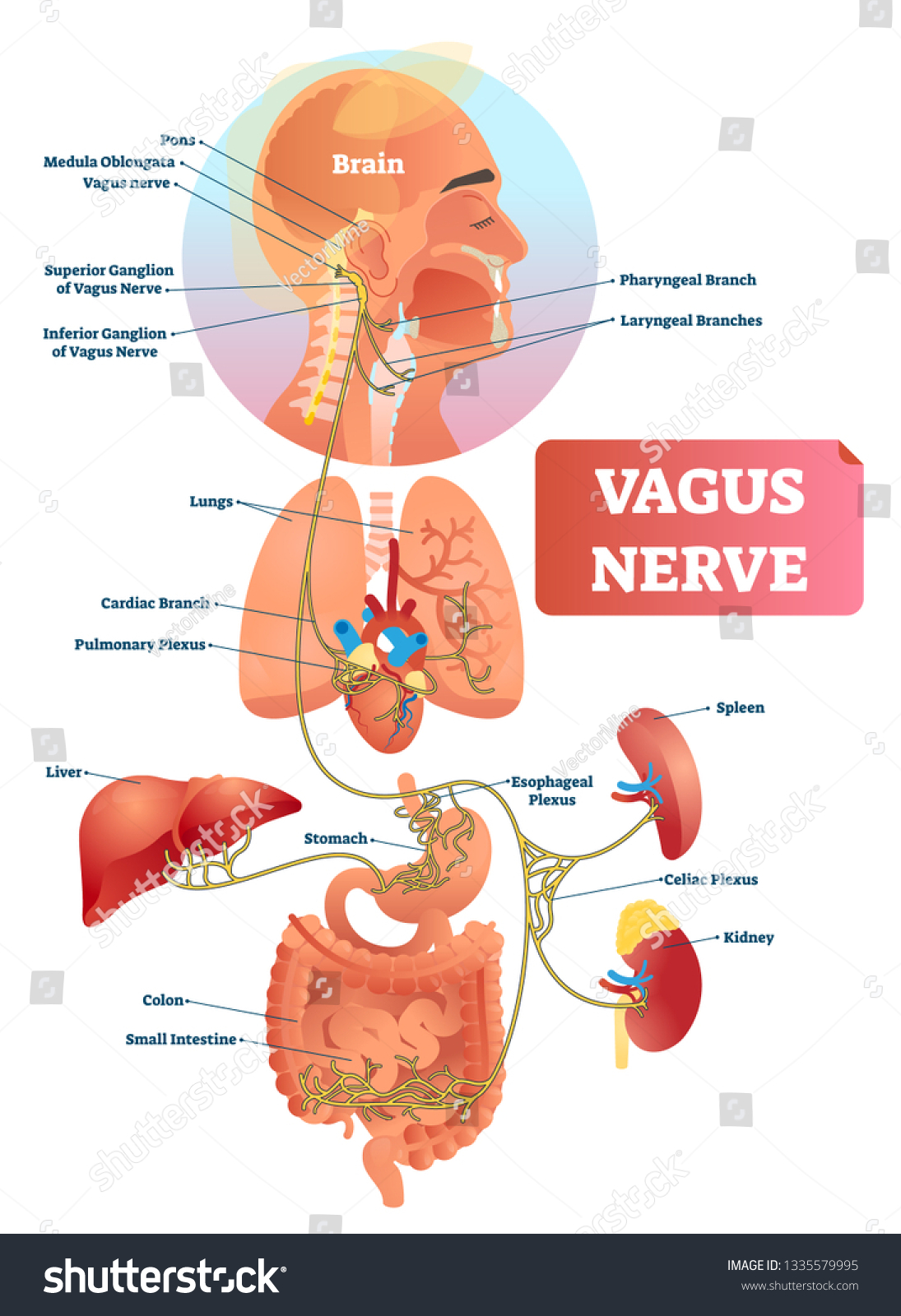

The vagus nerve — Cranial nerve X — is the longest nerve in the body. This nerve’s name comes from the Latin word “wanderer” because it seems to “wander” around the body. Many nerves are very specific and innervate only a few muscles or small areas. The vagus nerve innervates part of the tongue, the muscles of the throat, the heart and the entire digestive system, which is why it’s very important to the process of eating. Deep breaths help to lengthen and relax the vagus nerve. allowing all of these organs to function properly. The concept of “fight or flight” is too complex to fully discuss here, but imagine you are running from a lion chasing you. The last thing on your mind is to sit down to a leisurely meal. Deep, relaxing breaths shift us into the parasympathetic nervous system, making us calmer and more restful.

Cultural practices often seem to mirror natural/instinctual needs and processes. Praying, giving thanks or taking a deep breath before a meal all help us activate the parasympathetic nervous system so our bodies are receptive to food. The concept of being grateful also plays a role in activating the parasympathetic nervous system.

You’ve no doubt have heard the advice to “chew your food.” This, too, is an important biologic concept. Our teeth, which are designed to tear (incisors) and grind (molars) our food into a form that can be swallowed and digested, are by far the hardest part of our digestive system. They need to be used to do their job of physically breaking down food. We should chew meat 25 to 30 times, to ensure it is broken down, to be swallowed safely and more easily digested. No, I don’t expect anyone to chew mashed potatoes 25 times, but then again, you probably won’t ever hear me tell anyone to eat mashed potatoes in the first place. Food, especially meat, that is not properly chewed is more difficult if not impossible to digest. And this can lead to … indigestion! Medications, both prescription and over the counter, cost literally billions of dollars per year. So, chew your food and maybe spend less money on antacids.

The chewing process also alerts the rest of the gastrointestinal (GI) system that food is “on the way.” . Saliva adds digestive enzymes to the food to begin the chemical digestive process while the physical part is being performed by the teeth and chewing. In my years as a cancer doctor, I had a number of patients who needed feeding tubes or G-tubes in their stomachs. We often saw that patients were prone to regurgitate the tube feedings. I found that if I asked the patients to swallow a little bit of water or juice, or even to chew gum, before putting in the tube feeding, they were much less likely to regurgitate as they were simulating the more normal process.

Eating slowly is another important concept.

Unless you were literally “raised by wolves,” most of us face no real danger of our food being taken from us if we don’t eat it quickly enough. When we eat too quickly, we eat too much, often much more than we otherwise would. So, slow down, chew your food (yes, I do often count that I am chewing meat 25 times) and put your silverware down between bites. This is not a race — unless you are racing toward indigestion, poor bowel movements and obesity.

Sitting upright to eat facilitates swallowing and the function of the esophagus. Downing food while sitting hunched over on the sofa in front of the TV is not a good thing. Eating a meal at the table with family and friends has benefits that include the physical process, but also go way beyond that.

Finally, be thankful and thoughtful about the foods that you eat and how you eat them. If we put as much thought into our meals as we do in what to watch on TV, we’d be much healthier.